A very tiny book written by Charlotte Bronte at the age of 14, a miniature work, called The Young Men’s Magazine, is returning to the UK after being bought by the Bronte Society at auction in Paris. Experts at her museum suggest this section of the story is “a clear precursor” of a famous scene between Bertha and Edward Rochester in Jane Eyre, which Charlotte would publish 17 years later. A part of the Young Men’s Magazine paints a picture of a murderer driven to insanity after being haunted by his victim’s ghost and how “an immense fire” burning in his head causes the bed curtains to catch fire.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (1816-1855)

Type of work Psychological romance

Setting Northern England; 1800s

Principal characters

Jane Eyre, an orphan girl

Mrs Reed, Jane’s aunt, and mistress of Gateshead Hall

Edward Rochester, once-handsome owner of Thornfield Manor

St John Rivers, a young clergyman

Story overview

Orphaned at birth, Jane Eyre was left to live at Gateshead Hall Manor with her aunt-in-law, Mrs Reed. Jane remained at the estate for ten years, subjected to hard work, mistreatment and fixed hatred.

After a difficult childhood, the shy, petite Jane was sent to Lowood School, a semi-charitable institution for girls. She excelled at Lowood and over the years advanced from pupil to teacher. Then she left Lowood to become the governess of a little girl, Adele, the ward of one Mr Edward Rochester, the stern, middle-aged master of Thornfield Manor.

At Thornfield, Jane was comfortable with life – what with the grand old house, its well-stocked and silent library, her private room, the garden with its many chestnut, oak and thorn trees, it was a veritable palace. Mr Rochester was a princely and heroic master, and, despite his ireful frown and brusque, moody manner, Jane felt at ease in his presence. Rochester confided that Adele was not his own child but the daughter of a Parisian dancer who had deserted her in his care. Still, even with this forthright confession, Jane sensed that there was something Rochester was hiding.

Off and on, Jane heard bizarre, mysterious sounds at Thornfield. She finally discovered that Rochester kept a strange tenant on the third floor of the mansion. This hermit-like woman, once employed by Rochester – or so he said – often laughed maniacally in the night. And other disturbances soon followed.

One evening, after the household had gone to sleep, Jane was roused by the smell of smoke – to find Mr Rochester’s bed on fire. Only with a great deal of exertion did she manage to extinguish the flames and revive her employer.

Some time later, a Mr Mason from Jamaica arrived for a house party. Shortly after retiring that evening, Jane and the house guests were awakened by the sound of a man screaming for help. Rochester reassured his guests that it was merely a servant’s nightmare and persuaded them to return to their rooms. But Jane was obligated to spend the rest of the night caring for Mr Mason, who had somehow received serious slashes to his arm and shoulder. After hinting that he had obtained these wounds from an attack by a madwoman, he quietly left the house on the next morning.

One day Jane was urgently summoned to Gateshead: Mrs Reed was dying. Upon Jane’s arrival, Mrs Reed presented her with a letter from her childless uncle, John Eyre, requesting that Jane come to him in Madeira, as he wished to adopt her. The letter had been delivered three years before, but, because of her dislike for the girl, Mrs Reed had written John Eyre to inform him that Jane had unfortunately died in an epidemic earlier that year. Adoption by her uncle would have given Jane not only a family but an inheritance – one she still might claim. However, she decided to return to Thornfield.

One night, in the garden at Thornfield, Mr Rochester proposed marriage – and Jane accepted. She excitedly wrote to her Uncle John to tell him the news. But one month later, on the morning of her wedding day, Jane was startled from sleep by a repulsive, snarling old woman in a long, white dress and fondling Jane’s veil. Then, before bounding out the door, the wretch tore the veil to shreds. Jane’s groom comforted his shaken bride and Jane calmed herself and prepared for the marriage.

The ceremony was near its end; the clergyman had just uttered the words, “Wilt thou have this woman for thy wedded wife?” when a voice suddenly broke in: “The marriage cannot go on. I declare the existence of an impediment.” When asked for the facts, this man – a lawyer – produced a document proving that Rochester had married one Bertha Mason in Jamaica some fifteen years earlier. Mr Mason, the mysteriously wounded house guest, stood as witness to the fact that Bertha was still alive and living at Thornfield. At last Rochester stepped forward and acknowledged that the accusation was indeed true, but that his wife had gone mad; in fact, she came from a family of idiots and maniacs for three generations back. Rochester further maintained that this early wedding had been arranged by his father and brother in hopes that he would marry into a fortune.

The groom-to-be next invited the lawyer, the clergyman and Mr Mason to accompany him to Thornfield and see for themselves the woman to whom he had been bridled. Only then could they judge if he didn’t have the right to break this compact.

At the estate, Rochester led the company to the third-story room where his wife was kept. As he advanced toward a figure in the back corner of the room, “it grovelled, seemingly on all fours; it snatched and growled like some strange wild animal: but it was covered with clothing; and a quantity of dark, grizzled hair, wild as a mane, hid its head and face.” When Rochester finally restrained the raging, bellowing beast, he turned to the spectators and declared, “That is my wife.”

That night, Jane left Thornfield, bewildered and heartbroken. With the little money she had, she bought a ride on the first coach that happened by. After traveling for two days, she was dropped off at a remote crossroads and spent the night huddled in the heather. Her meager meals were made up of bilberries. Finally, the young woman found her way to Marsh End, the home of St John Rivers and his two sisters, Mary and Diana. They were very kind to the girl – who introduced herself as Jane Elliot – and nursed her back to health.

Then one day St John received word from Madeira that his cousin John Eyre had died, leaving twenty thousand pounds to his next of kin – Jane Eyre. The family lawyer was now trying to locate Jane through her uncle’s cousin, St John Rivers himself. Amazed and delighted to find that St John and his sisters were, in fact, family, Jane insisted on apportioning them a share of the inheritance.

Jane remained in the home of St John. One day, however, he came and expressed to Jane his long-felt desire to travel to India as a missionary, and asked her to accompany him – as his wife and assistant. Jane kindly declined his offer: St John did not love her as she wished to be loved. By some intuition, she sensed that she was needed elsewhere.

Then one night Jane had a vivid dream, in which Edward Rochester called to her and beckoned her to come to him. In response to the dream she returned to Thornfield. But upon her arrival, she found only a blackened ruin where the mansion had stood. At a nearby inn Jane learned that during harvest time a fire had broken out in the night at manor house. Rochester had desperately attempted to rescue his lunatic wife, who was on the roof screaming wildly and waving her arms. But just as he approached her, she had leaped to her death.

Jane rushed to the farm where Mr Rochester was now living, only to find her once strong and handsome master a lonely, helpless cripple. He had lost both his sight and his hand in the attempted rescue.

Jane’s love for Rochester was still strong, and she gladly chose to marry him. Eventually, sight returned to one eye, so that her husband could witness the birth of a son – who had obviously inherited his father’s once-fine features.

Commentary

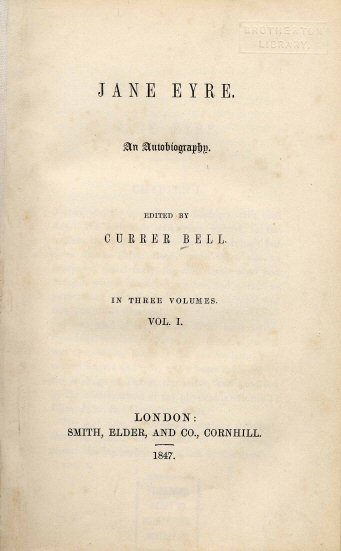

Because the publishing industry of the early and middle 19th century spurned female writers, Charlotte Bronte chose to work under the androgynous pseudonym Currier Bell.

Jane Eyre was written in the first-person, autobiographical form, allowing Bronte to draw the reader into her heroine’s plight. This was a successful approach, for even though critics point out some structural flaws in the book, it has always remained a highly popular work.

Jane Eyre is also an impassioned moral manifesto, as the Preface to the Second Edition makes clear:

Conventionality is not morality. Self-righteousness is not religion. To attack the first is not to assail the last.

The world may not like to see these ideas dissevered, for it has been accustomed to blend them; finding it convenient to make external show pass for sterling worth – to let white-washed walls vouch for clean shrines. It may hate him who dares to scrutinize and expose – to raise the gilding, and show base metal under it – to penetrate the sepulcher, and reveal charnel relics: but, hate as it will, it is indebted to him.