Summary of Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard

Summary of Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard

Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation (1981) is a seminal postmodern philosophical text that explores how reality, representation, and meaning have collapsed into a system of signs and simulations. It investigates the relationship between symbols, reality, and society in the context of contemporary media culture, arguing that in late capitalist societies, simulations have replaced reality, creating what he calls hyperreality.

Core Concepts

-

Simulacra

Baudrillard categorises simulacra into four historical stages:-

First-order simulacra: Representations that are faithful copies of reality.

-

Second-order simulacra: Representations that distort reality.

-

Third-order simulacra: Representations that pretend to represent reality but have no original reference.

-

Fourth-order simulacra: Pure simulation, where the representation has no relation to reality whatsoever, and becomes its own self-referential truth.

-

-

Simulation

Simulation is the process by which representations of things come to replace the things themselves. It is not a copy of the real, but becomes a truth in its own right. For Baudrillard, simulation is the dominant mode of representation in postmodern societies. -

Hyperreality

Hyperreality occurs when the distinction between reality and simulation breaks down. People live in a reality defined by simulations — for instance, theme parks, reality TV, and advertising create experiences that feel more real than actual reality, thereby supplanting it. -

The Precession of Simulacra

This refers to the way simulations do not reflect reality, but instead create their own logic and order. They precede and determine what we take to be real. Reality is then reconstructed through a lens of media, symbols, and simulations.

Cultural and Political Implications

Baudrillard argues that contemporary culture no longer engages with reality directly. Rather, individuals interact with signs and media, which construct a simulated version of the world. This has profound implications for politics, where media coverage can fabricate consensus or dissent, and for consumerism, where the sign value of products (status, image) overtakes their use value.

Examples Baudrillard Uses

-

Disneyland: A model example of hyperreality — it presents itself as fake to make people believe the outside world is real, when in fact both are simulations.

-

Watergate scandal: Instead of exposing corruption, its media representation served to reinforce the illusion of transparency and democracy.

-

The Gulf War: Later, in The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (1991), Baudrillard expands on his ideas, arguing that media representations of the war were so totalising that the war became a simulation rather than a real event.

Relevance

Baudrillard’s work has had a profound influence on media studies, cultural theory, and philosophy, and has been widely applied in critiques of advertising, digital culture, virtual reality, and post-truth politics. His ideas also influenced The Matrix (1999), which includes direct references to Simulacra and Simulation.

Baudrillard and The Matrix: Simulacra, Simulation, and the Illusion of the Real

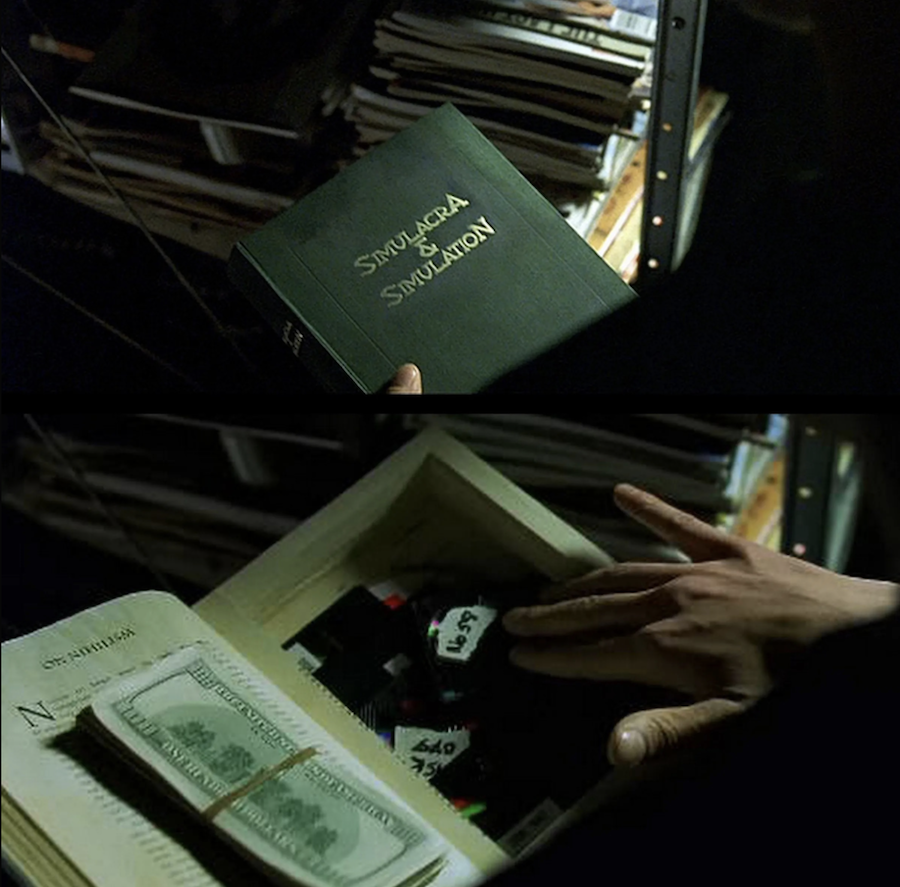

Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation is not only thematically resonant with the Wachowskis’ film The Matrix (1999), but it is also explicitly referenced in the film’s narrative architecture. In a symbolic gesture, Neo, the protagonist, uses a hollowed-out copy of Baudrillard’s book to conceal illegal software, suggesting that the philosophical framework it presents is more than a background reference — it is an integral code that informs the narrative logic of the film.

Baudrillard’s theory, particularly his notion of hyperreality, finds powerful visual and narrative expression in The Matrix. The film depicts a dystopian world in which human beings live within a simulated reality constructed by machines, while the true physical world has been devastated and rendered uninhabitable. This simulated world — “the Matrix” — is not simply a deceptive illusion, but rather a hyperreal system in which signs and codes have entirely replaced the referents they once denoted. As Morpheus tells Neo, the Matrix is “the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth,” a statement that could have been taken directly from Baudrillard’s theoretical lexicon.

The concept of the precession of simulacra — where simulations precede and determine the real — is embodied in the Matrix’s artificial environment. The film dramatizes Baudrillard’s assertion that simulations become more real than the real, ultimately erasing the distinction between reality and representation. The virtual world in The Matrix is so immersive and totalising that its inhabitants accept it as the only reality they have ever known. This directly aligns with Baudrillard’s fourth stage of simulacra, in which simulation becomes a pure simulacrum, no longer tethered to any original reality but instead generating its own internal consistency and authority.

However, it is worth noting that Baudrillard himself distanced his work from the film’s interpretation. In interviews, he remarked that The Matrix ultimately misrepresents his ideas by portraying the simulated world as something that can be escaped into a more authentic reality, whereas his own philosophy insists that there is no such authentic ground left — only further simulations. As he wrote, “The Matrix is surely the kind of film about the matrix that the matrix would have been able to produce.”

Despite this philosophical divergence, the film nevertheless introduces millions of viewers to a central concern of Baudrillard’s work: the destabilisation of reality in a media-saturated, technologically mediated world. Through cinematic spectacle and narrative allegory, The Matrix offers a cultural translation of Baudrillard’s postmodern critique — visualising the implosion of the real and the rise of a hyperreal order that governs modern life.

AI, Hyperreality, and the Collapse of the Real

Baudrillard’s vision of simulation finds striking relevance in the age of artificial intelligence, where generative technologies increasingly blur the line between reality and representation. Tools such as AI-generated images, deepfakes, and synthetic voices produce simulations that are not merely imitations but independent constructs, entities with no original referent. This reflects Baudrillard’s third and fourth orders of simulacra, where signs no longer represent reality but rather generate a hyperreality that supplants it. For instance, social media platforms curate a version of the world optimised for engagement, not truth, creating environments where the simulated becomes more believable, more desirable, and more influential than the real. The rise of AI companions, influencers, and content creators continues this trajectory, as people increasingly form relationships and experiences within artificially constructed realities. The hyperreal is no longer an exception but a condition of contemporary life.

The Simulation Hypothesis and Baudrillard’s Warning

The popular scientific and philosophical notion that our universe may itself be a simulation, a hypothesis explored by thinkers such as Nick Bostrom, ironically literalises Baudrillard’s critique. While Baudrillard’s concept of simulation was not intended as a physical or cosmological claim, but rather a sociocultural diagnosis, the overlap raises essential questions. If reality is coded, computed, or modelled, what remains of authenticity, presence, and the self? Baudrillard warned against the comfort of such simulated structures, where individuals cease to question the absence of reality beneath appearances. In a world where the digital becomes ontological, where reality is indistinguishable from its representations, we risk substituting critical inquiry for passive immersion. The simulation hypothesis, then, may be less a revelation of metaphysical truth than a symptom of hyperreality, a final substitution where even metaphysics is reduced to the logic of code and spectacle.

Reading as Simulation: Literature, Fiction, and the Hyperreal

Literature itself, especially the novel, can be understood as a refined simulation of life — a structured, symbolic world that mirrors reality through imagination, narrative, and metaphor. From a Baudrillardian perspective, novels are not merely reflections of the world but crafted realities with their own internal logic, emotional truths, and symbolic codes. They often produce hyperreal effects, where fictional experiences feel more poignant, more immersive, or more meaningful than real ones. In this sense, reading is a form of consensual simulation — a suspension of disbelief in exchange for emotional or intellectual resonance. Baudrillard’s critique invites readers to consider how stories shape perception, how characters become models of identity, and how genres create predictable emotional responses. Novels are maps of human experience that do not replicate reality, but organise and elevate it symbolically. Recognising fiction as a creative simulation enriches both literary interpretation and the reader’s awareness of how meaning is constructed and absorbed.

Neuroscience and the Brain’s Construction of Reality

Modern neuroscience supports the idea that what we perceive as “reality” is not a direct reflection of the external world, but rather a dynamic, brain-generated model based on sensory input, prior experiences, and predictive coding. The brain continuously interprets incoming data through a framework of expectations, effectively generating a simulation of reality rather than passively receiving it (Friston, 2010; Clark, 2013). This aligns intriguingly with Baudrillard’s notion of simulation, suggesting that the experience of reality is always mediated — whether by neural architecture or cultural symbols. Research in perceptual neuroscience shows that up to 90 percent of what we “see” is predicted by the brain before visual information arrives from the eyes (Bar, 2009). Our perceptions are not objective recordings but constructed narratives, influenced by attention, memory, emotion, and context (Seth, 2021). Thus, the perceived environment — whether a room or a virtual space — is always co-created by the observer’s internal model, offering a biological foundation for understanding hyperreality as not only cultural, but cognitive.

Key Quote

“Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being, or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal.”

“To simulate is to feign to have what one doesn’t have.”

“The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth—it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true.”

“We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning.”

“Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real.”

“The transition from signs that dissimulate something to signs that dissimulate that there is nothing, marks the decisive turning point.”

“When the real is no longer what it was, nostalgia assumes its full meaning.”

“The era of simulation is inaugurated by a liquidation of all referentials—worse: with their artificial resurrection in the systems of signs, a material more malleable than meaning itself.”

“Television knows no night. It knows no downtime. It is a perpetual screening machine.”

“We are in a logic of simulation which no longer has anything to do with a logic of facts and an order of reason.”

“It is the real that has become our true utopia—but a utopia that is no longer in a place, but in a sign.”

“It is dangerous to unmask images, since they dissimulate the fact that there is nothing behind them.”

Reference

Baudrillard, J. (1981). Simulacres et simulation. Paris: Éditions Galilée.

[English translation: Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation (S. F. Glaser, Trans.). University of Michigan Press.]

https://archive.org/details/simulacra-and-simulation-1995-university-of-michigan-press/mode/2up

Bar, M. (2009). The proactive brain: Memory for predictions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1521), 1235–1243.

Clark, A. (2013). Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind. Oxford University Press.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

Seth, A. (2021). Being You: A New Science of Consciousness. Faber & Fab

Table of Contents of Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard

-

The Precession of Simulacra

-

History: A Retro Scenario

-

Holocaust

-

The China Syndrome

-

Apocalypse Now

-

The Beaubourg Effect: Implosion and Deterrence

-

Hypermarket and Hypercommodity

-

The Implosion of Meaning in the Media

-

Absolute Advertising, Ground-Zero Advertising

-

Clone Story

-

Holograms

-

Crash

-

Simulacra and Science Fiction

-

The Animals: Territory and Metamorphoses

-

The Remainder

-

The Spiraling Cadaver

-

Value’s Last Tango

-

On Nihilism