Rhizomapping, Rhizomaps, Rhizomatic Learning – New ways to take and make notes and learn more effectively with mindmapping and rhizomapping – Speed reading tip 17: Take notes with mindmaps and rhizomaps

Speed reading technique 17: Take notes with mindmaps and rhizomaps

Summary Taking notes is the first step to fixing information in your memory. Mindmaps and rhizomaps are more memorable and lead to greater creativity than linear notes. If you’re away from your desk, then write notes (on post-its) in your book.

A tried and tested way of helping you remember what you read is to take notes. It engages your mind which makes it easier to take in information – you have to think critically to decide which notes to write. Noting which ideas are important to you helps fix them in your brain – and therefore helps you remember them. Also the physical act of writing itself helps form memories, since it brings into play additional parts of the brain and helps embody the information.

We suggest two ways of taking or making notes which improve on traditional linear note-taking:

- mindmapping (developed by Tony Buzan)

- rhizomapping (developed by Jan Cisek and Susan Norman based on philosopher Giles Deleuze’s work on rhizomatic thinking)

There is a difference between note-making – generating ideas yourself – and note-taking – taking ideas from other sources such as books or lectures. You can use both mindmaps and rhizomaps for either.

Mindmapping

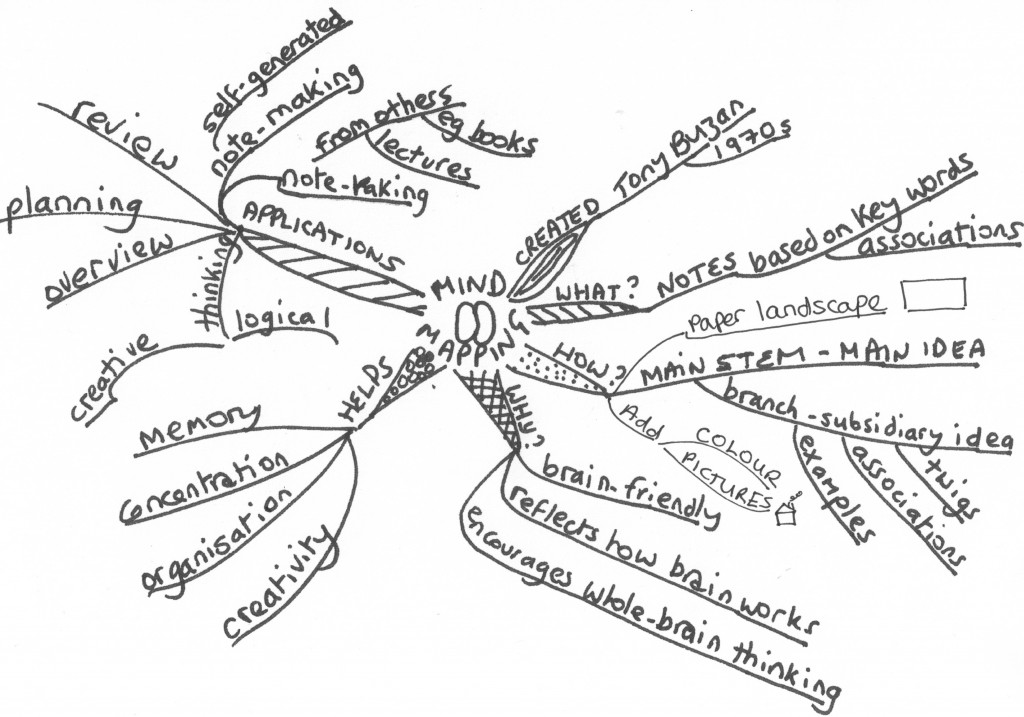

A mindmap (see example below) starts with a picture or key word in the centre to represent the topic. Main ‘branches’ radiate out from the key word. On each branch is written a word or short phrase which encapsulates a key idea relating to the topic. Secondary ideas and examples are summarised on smaller branches and ‘twigs’ radiating out from the branches. Ideally use colour and pictures to make your mindmap more memorable.

The key to a good mindmap is to formulate your ideas clearly in the minimum number of words and use the branches and twigs to show relationships between ideas.

When to use mindmapping Mindmapping is very good for showing the connections between ideas. Produce a mindmap

- to set up a structure as a starting point for a 20-minute work session (read speed reading technique 18) or syntopic processing (read speed reading technique 22)

- to clarify what you already know about a subject (and to identify possible gaps in your knowledge) before you start reading – as you read you add to the mindmap

- any time you are taking notes when you already know the structure of the subject and how things do (or are likely to) fit together

- for sequential, step-by-step notes

- to organise the ideas from random notes (or from a rhizomap) so you can present them to someone else (eg to give a presentation or write an essay or a report)

For more information on mindmapping, google ‘mindmapping’, or ‘Tony Buzan’.

Buzan gives additional rules, such as only writing one word on each line, colour coding each branch, etc. We have found that the technique is effective even without following these secondary rules and may even be better when you make the technique your own.

This is a mindmap about mindmapping.

Rhizomapping

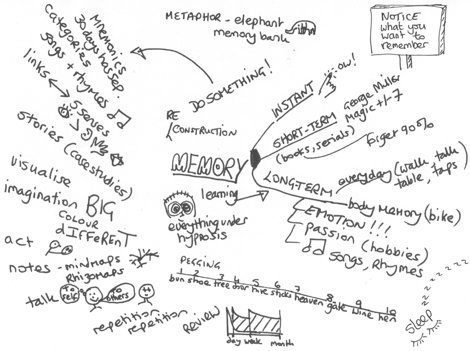

With a rhizomap, you initially jot down ideas randomly on the page, and as you see additional ideas (or quotations, or examples) which seem to link with something you have already written, you write them nearby. If appropriate, you can reorganise the ideas afterwards by highlighting key ideas, or linking ideas using numbering, colour coding, stars, arrows, underlining, etc.

When to use rhizomapping Use rhizomapping when you do not know the structure of the subject before you start, eg when you are getting to grips with an overview (read speed reading technique 25) of a completely new subject, or when you are not sure what useful information you will get from a book.

A rhizomap can also be a good way of presenting information, for example, this rhizomap presents key ideas on memory.

Tips

For both rhizomaps and mindmaps:

- Choose your key words carefully. Make sure they summarise the ideas succinctly in a way which will remain meaningful to you when you look back later.

- Use colours, quick pictures and symbols to make your notes more memorable.

- Research with children has shown that mindmaps are significantly more effective and memorable if the author of the mindmap explains the information in them to someone else as soon as possible after finishing it (see talking – read speed reading technique 19).

- By all means jot down page numbers so you can easily refer back to books, but make sure you link the page number to a key word or idea so you know what it refers to. A list of unconnected page numbers is of very little use.

Differences between mindmaps and rhizomaps

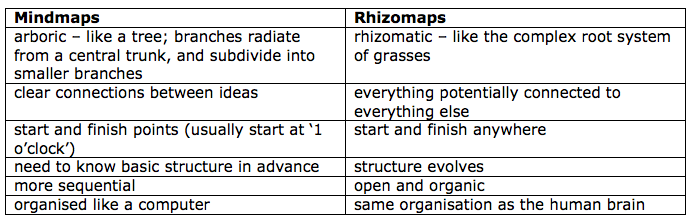

| Mindmaps | Rhizomaps |

|---|---|

| arboric – like a tree; branches radiate from a central trunk, and subdivide into smaller branches | rhizomatic – like the complex root system of grasses |

| clear connections between ideas | everything potentially connected to everything else |

| start and finish points (usually start at ‘1 o’clock’) | start and finish anywhere |

| need to know basic structure in advance | structure evolves, process oriented |

| more sequential | open and organic |

| organised like a computer | same organisation as the human brain |

| left brain | right brain |

Rhizomapping / Rhizomap

(Procedure devised by Jan Cisek and Susan Norman, term coined by Hugh L’Estrange) Random way of making and taking notes. A rhizome is a plant (like grass) which spreads through its root system and springs up in many different places. It doesn’t have a central stem and it is very robust. (The internet works kind of rhizomatically.) The concept of rhizome was originally developed by a French philosopher, Gilles Deleuze.

Make or take notes haphazardly on the page. Afterwards, look back at the notes and make links between them, by circling or underlining things in different colours, or drawing lines between them. It is often easier to make a rhizomap when you are not sure in advance what the key ideas are going to be. Once you have made your rhizomap, you might find it satisfying to reorganise your notes into a more coherent mind-map … or you might not! (This idea is currently unique to Spd Rdng.)

Note-taking is an important step in helping you remember what it is you’ve read. Whether or not you refer back to the notes, the activity itself involves making decisions about what it important, and rephrasing the ideas into a shorter form – which helps the ideas crystalise. These ‘crystals’ stick in the brain much more than ideas you have just understood receptively as you have read them.

Rhizomatic Learning

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhizomatic_Learning

Rhizomatic thinking

According to Claire Colebrook, who’s probably the best writer on Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the rhizome suggests that the rhizome is a connection without any specific mediation, so it goes in all directions – they branch out, they stop, they branch out in other connections. Rhizomatic means not presuming the ground for connections. So it puts the connections and relations as a question, not a foundation. For example, anthropologists assume a ground for connection based on “we all are variants of the human”. The rhizomatic says, “we don’t know yet, what relationship or connectedness we have”.

and from Claire Colebrook’s book Understanding Deleuze

“Rhizome/Rhizomatics

Deleuze and Guattari explain these terms by first distinguishing between the ‘rhizomatic’ and the ‘arborescent’ (Deleuze & Guattari 1987). Traditional thought and writing has a centre or subject from which it then expresses its ideas. Languages, for example, are seen to share a basic structure or grammar which is then expressed differently in French, German or Hindi. This style of thought and writing is arborescent (tree-like), producing a distinct order and direction. Rhizomatics, by contrast, makes random, proliferating and decentred connections. In the case of languages we would abandon the idea of an underlying structure or grammar and acknowledge that there are just different systems and styles of speaking, that the attempt to find a ‘tree’ or ‘root’ to all these differences is an invention after the fact. A rhizomatic method, therefore, does not begin from a distinction or hierarchy between ground and consequent, cause and effect, subject and expression; any point can form a beginning or point of connection for any other. (This is typical of Deleuze and Guattari’s own method. They do not use philosophy to interpret biology or biology to explain philosophy; they allow the two styles of thinking to mesh, transform and overlay each other.) Further, they insist that what looks like a binary or opposition in their thought—such as the distinction between rhizome and tree—is not an opposition but a way of creating a pluralism. You begin with the distinction between rhizomatic and arborescent only to see that all distinctions and hierarchies are active creations, which are in turn capable of further distinctions and articulations.”